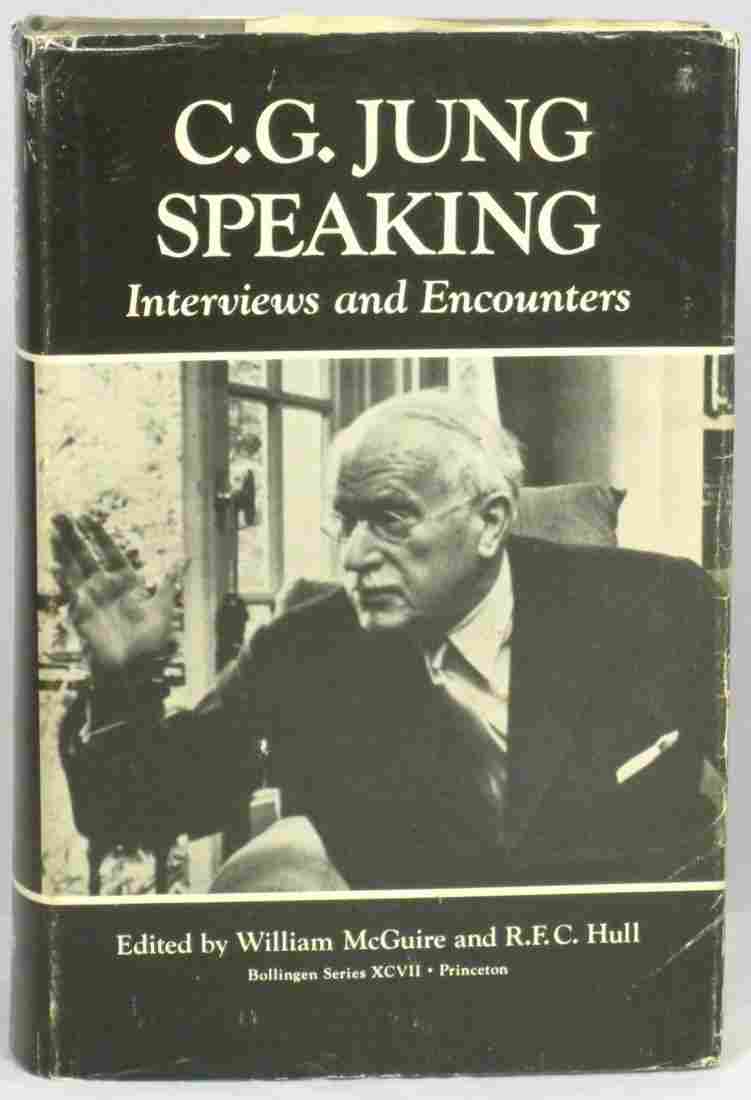

C.G. Jung Speaking : Interviews and Encounters

《C.G. Jung Speaking : Interviews and Encounters》里有一段卡尔·荣格对于四十岁的观点:

A man who after forty years has not reached that position in life which he had dreamed of is easily the prey of disappointment.

Hence the extraordinary frequency of depressions after the fortieth year.

It is the decisive moment; and when you study the productivity of great artists一for instance, Nietzsche-you find that at the beginning of the second half of life their modes of creativeness often change.

For instance, Nietzsche began to write Zarathustra, which is his outstanding work, quite different from everything he did before and after, when he was between 37 and 38.

That is the critical time. In the second part of life you begin to question yourself.

Or rather, you don’t;you avoid such questions, but something in yourself asks them, and you do not like to hear that voice asking “What is the goal?”

And next, " Where are you going now?"

When you are young you think, when you get to a certain position, “This is the thing I want.”

The goal seems to be quite visible.

People think, " am going to marry, and then Ishall get into such and such a position, and then shall make a lot of money, and then I don’t know what"

Suppose they have reached it; then comes another question: “And now what?

就是说人生在四十岁之前向外扩张,去探索去追求,但是如果在四十岁后还没有达到他梦想的生活地位,就会被失望吞噬,所以人四十岁以后得抑郁症的比率非常高。

一些伟大的艺术家,在四十岁左右会发生一次变化 ,比如尼采就是三十七八岁时开始写《查拉图斯特拉如是说》的。中国历史上的文人也一样,基本上都是要经历一些人生跌宕,然后蜕变成长的,作品风格也会发生巨大的变化,通常成就也会提升一个层次。

所以不管是年龄还是经历,人生总有一些点会让人蜕变,或让人认命,后者是大多数。

在人生的下半场,我们不可避免会开始质疑,但同时也需要重新设立目标,而不是被动等待那个最终的结局。

孔子说“后生可畏,焉知来者之不如今也? 四十、五十而无闻焉,斯亦不足畏也已。”,那是因为古人平均寿命短,五十已是暮年,不能拿来当件混吃等死的借口。